At this time of year, I like to spend some time looking back at what I made, what I learned, and how much progress I made on the goals I set myself for the year. I putter around and declutter the studio and hope that helps to declutter my mind for the new year. Maybe you do something similar?

This year I added a new approach: scrolling back through all the photos on my phone, to see what struck me enough that I took a photo (or several). Perhaps there are clues there too for the way into 2023. If this sounds like something that might be useful, read on . . .

I found lots of process photos of pieces I worked on. I'm especially pleased with the pieces below as they seem to point in the direction I want to go. I'm noticing a shift toward black/white/gray and neutral tones. (Perhaps living with a black-and-white photographer for 30+ years is finally rubbing off?) As you look back at your work, what are you proudest of? What would you like to do more of in 2023?

|

| Ashfall, (c) Molly Elkind 2022, linen warp, paper, grasses, ashes, matte medium. Weaving 18" x 7" including fringe; shadowbox 18.5" x 12" x 3". |

|

| Dark Sky, (c) Molly Elkind 2022, linen warp, paper weft. Weaving 7" x 6" including fringe, farmed to 13". 13" |

|

| Woven Grasses Study, (c) Molly Elkind 2022. Weaving 18" x 6.25" including grasses and fringe. Framed to 21" x 17". |

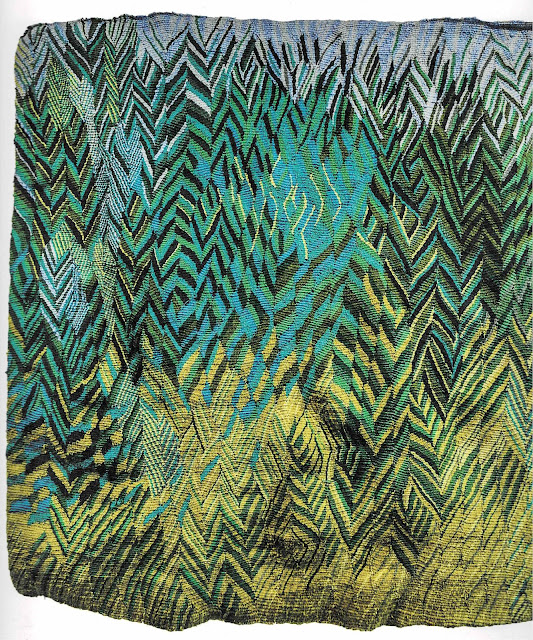

I've completed the SkyGrass series with several small pieces, all but one of which sold. In retrospect I see that these pieces paved the way for me to weave with actual grass instead of depicting it with yarn, something I plan to do more of. But they were worth doing in themselves, too, and I’m proud of them.

|

| Blue Grama 4, (c) Molly Elkind 2022, linen warp, wool, linen, Japanese ramie bark, cotton floss. Weaving 5" x 5", framed to 13" x 13". Sold. |

|

| MountainGramaGrass, (c) Molly Elkind 2022. Linen warp; wool, silk, linen, Japanese ramie bark, cotton Weaving 9.75" x 7", framed to 21" x 17". Sold. |

I saw a number of exhibits of art in various mediums. These have continued to reverberate in my mind, months later:

Alma Thomas at the Frist Museum in Nashville. Thomas was an important African-American abstract painter whose work was mostly founded on a love of pattern inspired by the natural world.

|

| Alma Thomas, Babbling Brook and Whistling Poplar Trees Symphony, acrylic on canvas, 1976. |

Susan Iverson, the Color of No at the Surratt Gallery at Vanderbilt University, Nashville. See my blogpost about this exhibit here. I was struck by the cumulative power of one concept, explored in depth, investigating particularly the power of color to change meaning.

|

| Susan Iverson, The Color of No, installed at the Surratt Gallery, Nashville, TN. |

John Paul Morabito, The Immaculate Collection: A Queer Tangent in Tapestry at Indianapolis Art Center. John Paul had me right away with their focus on images of the Virgin Mary, specifically re-conceived images drawn from paintings by Raphael. They have souped up the colors and used Jacquard technology to transform the surface into beautifully complex mixes of pattern. I found the work disturbing, fascinating, mysterious and unforgettable.

|

| John Paul Morabito, Left: Madonna di San Sisto, 2020, cotton, wool, glass beads Right: Madonna del Cardellino, 2019, cotton, wool, glass beads, gilded masonry nails |

At Convergence in July, I was intrigued most of all by the power of baskets in HGA's juried exhibit of basketry, Dogwood to Kudzu. The strong object-hood (I don’t know how else to describe it) of 3D pieces using natural materials is continuing to cast a spell over my current explorations. Read my blogpost here.

|

| Judy Zugish, Daughter on the Mountaintop. |

I saw some intriguing Northwestern native baskets in the Chihuly Museum in Seattle and fell in love with the fine patterns and intricate workmanship, again appreciating the power of the empty vessel form and the exquisite workmanship.

|

| Apologies; no further information available |

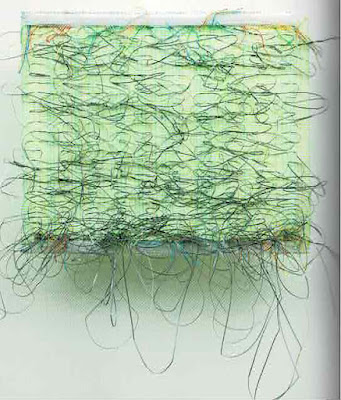

At the ATA Members' Retreat and Workshop with Jennifer Sargent in July, I was intrigued by Jennifer's use of varied setts and open, balanced weave in her work. I am continuing to explore this in my own work.

|

| Jennifer Sargent, woven sample |

Finally, there were several books that have led me to think more deeply about the practice of tapestry and weaving. I suspect one or two of these might be on your own list of such impactful books, too. What other books influenced your thinking this year?

Solveig Aalberg, Continuum. A powerful example of the cumulative impact of a series of small textiles woven to a system. Read my post here.

Howard Risatti, A Theory of Craft: Function and Aesthetic Expression. An academic work of art/craft theory. Risatti carefully and logically builds an argument that craft and art are not the same and should not be collapsed into the same category. For a long time I had thought that only by arguing that there was no fundamental difference between the two could craft take its place equal to art in the minds of the public, curators, etc. Risatti explicates the real and important differences between the art and craft (and demonstrates that they are not tied to function or to materials as is commonly thought), and ultimately argues for a special category called "critical objects of craft." These are the works based in craft materials and/or techniques that innovate, question and push the boundaries of their medium. If theory is your jam, check out this book.