I've been deep in class preparation mode for the past few months, developing five new lectures and workshops for the Weavers Guild of Minnesota. It's been fun and I'm learning a lot; I only propose classes on topics that I know will teach me something! So I've been looking at lots of tapestries in books and online and thinking about all the widely varied approaches to the medium today. It's an exciting time to be a weaver, with so much inspiring work, varied materials, and a wide range of looms from tiny to huge, available to choose from. It can be overwhelming to have so much choice, so many options!

If you've read this blog for long you know that I am continually experimenting, trying to figure out what my voice is in tapestry, what is my own tapestry language. For it is a language, a way of describing life using the grammar of the loom and of weft-faced weaving. It takes time and practice to become fluent in a new language. I have been at it for 13 years now and I'm just beginning to feel somewhat fluent. Recently I came across an excellent blog post on this subject by master weaver Joan Baxter on the British Tapestry Group blog: "Tapestry in its own words: what is the native language of tapestry and how can we best design for it?" So much of what Joan writes resonated with me. Please, go read it!

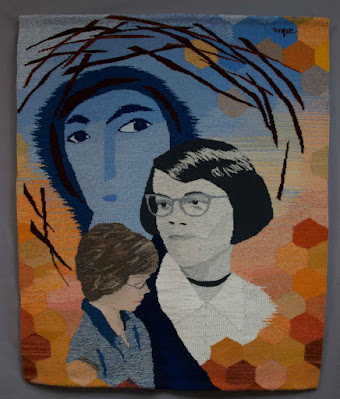

It occurred to me during my class research that so many of the classical, traditional tapestries were in what I'd call the mythical mode: they told grand stories of gods and creation, history and war and empire-building. They explained societies and cultures to themselves by telling important stories. These tapestries are the woven equivalents of the Iliad, the Odyssey, Paradise Lost and War and Peace in literature. Or, more currently, Game of Thrones. The classical works were large murals, but contemporary tapestry artists show it's possible to work in the mythical mode on a smaller scale. I've seen work recently by Frances Crowe about Covid and the plight of refugees that qualifies. You can also look up Murray Gibson, Elizabeth Buckley, Chrissie Freeth and Barbara Heller, among many others working in a contemporary mythical mode. I worked in this mode myself when I made a series of work about the image and impact of the Virgin Mary.

|

| Molly Elkind, Mary (the anxiety of influence), 2017. 45" x 37" |

Sticking with the literary metaphor, there is also the lyrical mode, the mode of poetry, the mode in which we express aspects of our own experience and emotions. I suspect this is where most of us conceive of our work. The lyrical mode allows us to respond with joy or grief or exhilaration or rage to what we see in nature and in the world around us. Here a smaller format often feels right to me, though not always. I went down a rabbit trail not long ago in which I read up on haiku, the 3-line Japanese poetic form, and I conceived of my recent small open warp experiments as woven haiku.

|

| Molly Elkind, Open Warp Vista: Roots, Rain (c) 2020 |

The poetic, lyrical mode calls for the uniquely individual expression. If you weave a tapestry diary, or make woven doodles ("woodles" as some call them), or delight in making endless samples (that would be me) you are experimenting with weaving in this mode. You are pushing our tapestry language to speak as poetry does, in a fresh, insightful, emotional way. When you dye your yarn to achieve just the right color or gradation--when you spin your own yarn or source yarns with unusual fibers and textures--when you exploit or disrupt the grid that the loom gives us--I would say you are weaving in the lyrical mode. You are making work that is about your own response to what is given, whether in the loom or in the world. There are too many artists working in this mode to name them all here, but check out ATA's Artist Pages for inspiration.

The small studies I've called "minimes" are also in the lyrical mode, capturing a brief moment of perception, emotional response, or a deeply-felt engagement with the medium and materials.

|

| Molly Elkind, detail Snow (c) 2020 |

|

| Molly Elkind, detail, Zion (c) 2020 |

At this moment the lyrical mode for me involves disrupting and varying the woven surface with varied textures, with open and eccentric weaves, with collaged elements. It involves juxtaposition and fragmentation, and it involves the quest to make objects not pictures--to make something that can only be woven and cannot exist in another medium. Joan Baxter writes, "A tapestry should only be woven if it cannot exist in another medium and the medium should somehow be intrinsic in the design from the start." This is a tall order. Most of us design our tapestries by drawing, painting or collage-ing, and then translate them into tapestry. Like Joan, I am trying to be brave enough to work now without a fully resolved drawing or cartoon, but to trust the weaving process to tell me what I need to do. I've noticed for a long time that my samples and experiments are often more exciting and appealing than tapestries woven from cartoons I have labored over. Hmmm. What does that tell me?

|

| Molly Elkind, Peachtree Boogie Woogie (c) 2021 |

I'm curious to hear your own thoughts on these ramblings. What mode do you like to work in--mythical, lyrical, or something else? Which artists do you admire who work in the mythical or the lyrical modes?

Molly, thank you for such a thoughtful post. I am just returning to my tapestry practice and this post helps me think about my weaving in a different

ReplyDeleteway. Be well and happy weaving. Michiele