If you've followed this blog for long you know I love to look back and to look forward as we approach the end of a calendar year. I truly believe the best information about our personal and studio goals for the next year are to be found in reflecting on what we've done, not done, succeeded at--and failed at--in the recent past.

This year I decided to take a twist on my usual approach, where I look at the extremely . . . um, optimistic goals I set back at the beginning of the year and note ruefully how many of them remain unaccomplished.

This time I thought I'd be super-specific and quirky about this exercise in a way that is fun and maybe even inspiring for you to read as you look backward and forward for your own practice.

So here are some questions you can ask yourself, and my own answers at the bottom, if you're interested.

1. What did you make this year that you are proudest of? And (here's the really important part) Why? Why did you make it? Why are you proud of it? Do you want to make more like this?

2. What rabbit hole(s) did you go down that turned out to be fruitful? Or that turned into dead ends, but necessary ones?

3. Did you travel anywhere that inspired you? What exactly inspired you? The scenery? The art or craft you saw? The people? How can you bring that into your practice?

4. If you read any helpful books or articles this year, what were they? How did they inform your practice?

5. Did you use any new materials in your work? This can range from something as simple as silk instead of wool weft, or linen instead of cotton warp. . . or something more unusual like plastic or paper or wire in your weaving. Will you continue to explore these or other new-to-you materials? How can you choose your materials for their own expressive potential?

Of course the questions you ask yourself really depend on your own grounding assumptions about why you do what you do in the first place--what you hope to experience as a result--or in the process--of your weaving. So that's a useful question too. I find it helpful to journal about these things (I'm a wordy person) but you may prefer just mulling them over as you overunderoverunder, or talk about them with weaving or art friends.

Here are my own answers to the questions.

1. Piece I made in 2023 that I'm proudest of, and why.

|

Molly Elkind, canoe study. Wire, various fibers, blue grama grass, plastic survey marking whiskers

|

This piece was tedious as all get-out to make. I set up a small pin loom on foamcore with some nails, in the shape of a flattened canoe pattern. I wove the piece in lots of little patches of different yarns, all of whose ends had to be tucked or sewn in. I inserted the grass as I wove and tried really hard not to break it as I worked. And then I removed it and stitched the seams that formed it into a canoe. Every single thing about it was fiddly . . .and I hate fiddly! And yet . . . I really like it and am planning to make more such vessels, and to make them larger. There you go.

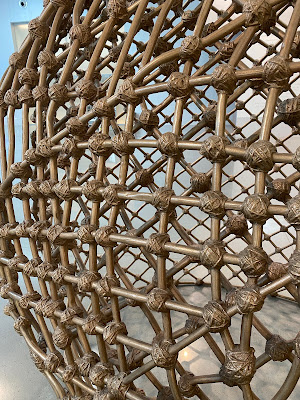

2. Deepest rabbit hole that ultimately led to a dead end for me: basket-making. As

I became interested in making 3D forms I realized basket makers solved

this mystery millenia ago, and that their weaving techniques might prove

fruitful for me. I experimented with making a few small baskets and

soon realized this was a much more challenging and deeper medium than I

had thought. (I seem to re-discover on an almost daily basis how humbling weaving of all sorts can be!) I decided to stick with what I know, cloth-like weaving, and continue

to explore its 3D potential.

I'm not showing you the really sad little twined experiment that convinced me to stick to weaving.

3. Most inspiring travel: It was a crazy-busy year for travel for me, never to be repeated! I

was fortunate to see gorgeous landscapes in Iceland, in Nova Scotia, and in France. But

for my work, the tapestry tour to France has been the most influential on my current

thinking. I also keep thinking about the art I saw in Houston on a teaching jaunt to the Contemporary Handweavers of Texas conference. (I wrote in previous blog posts here and here about the tapestry tour and here

about the amazing art to be found in Houston.) Mark Rothko's Chapel

paintings continue to haunt me, with their dark but not wholly black

palette. Most of all, I'm haunted by this image from the Apocalypse tapestry in Angers.

|

Apocalypse, detail: The Second Trumpet: The Shipwreck, commissioned by Louis I of Anjou, designed by Jean Bondol, made by once-known weavers in the workshop of Robert Poisson, 1373-1382.

|

For me this image, with its fire from the sky and on land, its perfect storm tossing people into the sea, is an apt metaphor for the climate disaster we face in our own time. My current work is about this.

4. Best book purchase: Baskets as Textile Art by Ed Rossbach. Despite what I said about basketry not working out for me, this quotation from it now resides on my studio wall:

"The perishable thing which survives speaks most potently of time, of all time rather than the moment of its existence." --Ed Rossbach, p. 49.

The book was published decades ago but it provided useful context for the moment in which approaches to basketry moved toward sculpture. Beyond that, though, I love to ponder the paradox, expressed so well here, that fiber work is both supremely perishable. . . and can, against all odds, last hundreds of years.

As it happens, it's impossible to choose just one "best book" for me, for 2023. Here's a few more:

The Apocalypse Tapestry of Angers, Liliane Delwasse. Also: Front and Back: The Tapestry of the Apocalypse by Francis Muel. I am currently obsessed with this tapestry. These books are instrumental in my understanding of this amazing work.

Martin Puryear: Multiple Dimensions. I saw one of Puryear's pieces in Houston and really loved it. Then I saw him featured on PBS' Art 21 and now I appreciate even more his craft-based approach to sculpture. His forms are abstract but so evocative.

I've splurged on a couple of catalogs from the well-known craft gallery browngrotta and they have given me new food for thought in terms of 3D form and technique: An Abundance of Objects and Influence and Evolution: Fiber Sculpture . . . then and now. More catalogs are on my wish list for Santa. These catalogs allow me to broaden my perspective by looking at some of the most elegant and beautiful craft-based work being done in the world today.

5. Weirdest new-to-me material used in weaving: I've been using a number of non-fiber materials in my weaving the last couple years--dried grasses, wire, plastic. I am far from the first weaver to use these but for me they feel weird and challenging--and tremendously exciting for their expressive potential. I explored a number of books about weaving with wire and natural materials: Weaving with Wire by Christine K. Miller and Wild Textiles by Alice Fox. The classic in the field is Textile Techniques in Metal by Arline M. Fisch.

|

Molly Elkind, Bivium study. Wire, wool, linen, survey marking whiskers. 2023.

|

This standing panel is another direction I want to explore in 2024. Where does your work this year point you for next year?