Note: If you are a member of the Handweavers Guild of America (HGA), you may have seen a shorter version of this review in the most recent issue of the magazine for members, Shuttle Spindle Dypepot. Here I expand on that review with additional thoughts. I am grateful to HGA for allowing me to review this book and urge you to join if you are not already a member.

I am thrilled to recommend wholeheartedly this book about a figure so influential in modern tapestry that he is known among weavers by just his first name: Archie. Though I never had the privilege of meeting or studying with him, I will presume to use his first name here. This book, by "Archie Brennan as told to Brenda Osborn," compiles many of Archie's writings, his memoirs about his life, travels, and career, and best of all many photographs of his work. If you are a tapestry weaver you absolutely need this book to understand contemporary tapestry. And if you're not a weaver, I bet you'll still find the book fascinating for the details of Archie's life and training and for his thoughts about how weaving and fiber art connect to the wider art world, and simply put, how pictures are made.

|

| Published by Schiffer Publishing 2022; widely available |

Brenda Osborn was a longtime member of the "Wednesday Group" of weavers who gathered with Archie and his partner, weaver Susan Martin Maffei, on a regular basis for years to learn together. The book is clearly a labor of love and a testament to a weaver and teacher who had a profound impact on all his students, and on the students of those students. If you are new to the field or like me, want to study "with" Archie, go HERE to learn more. This website has a link to a series of videos Archie made that are incredibly detailed demonstrations of tapestry tips and techniques. I know several weavers swear by them.

It was deeply thought-provoking to study the images of Archie's work and to read his writings. I find much to agree with. For example, Archie describes his work as "graphic, pictorial, often narrative" but always "a creative journey of discovery rather than a reproduction of a prepared design." For me, weaving is definitely a journey of discovery, each and every time, but it's rarely narrative or even pictorial in the usual sense. While I would love to get to the point of being skilled enough to weave without a cartoon, as Archie did, I'm not (usually) there yet. And to be clear, Archie always did numerous studies and sketches that informed his pieces. But his larger point has hugely influenced weavers today: that the imagery in tapestries should appear as if it could only have been made by weaving, not by painting or photography or any other medium. Archie championed the individual artist/designer-weaver, even though he apprenticed at the Dovecot Studios in Scotland and helped to found the Australian Tapestry Workshop.

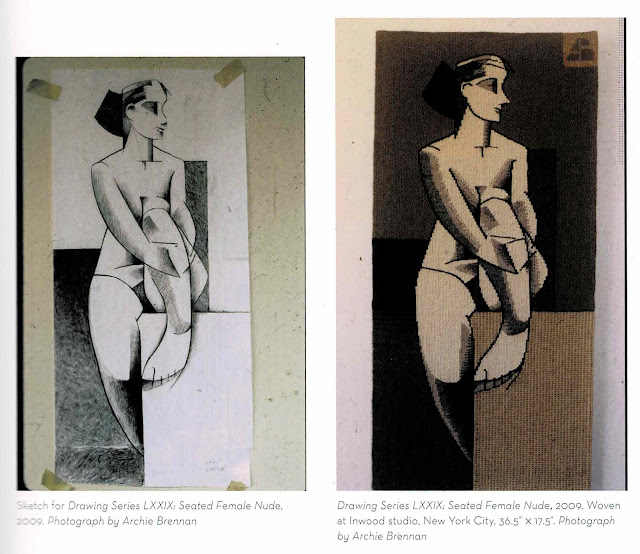

Archie writes that his work has been "a continuous search for a personal graphic language, the nature of woven drawing that is unique to tapestry." I think most practicing weavers would agree that their work is an ongoing search for a personal voice and vocabulary in tapestry. Archie's reference to drawing gets at a key point: during his seven-year apprenticeship at the Dovecot, Archie was required to attend drawing classes four times a week. Drawing remained a lifelong practice and the bedrock of his tapestry work. He participated in life drawing sessions with live models for years. Archie's genius is fully evident in the Drawing Series of tapestries based on these sketches. They masterfully simplify line and shape in a way that honors and emphasizes the grid of the loom. Rather than weaving from the side in order to smooth out steep vertical curves, he wove from the bottom up and exaggerated the "steppiness" of these lines. Archie's love of the drawn line--and perhaps his color-blindness--explain a great deal about his own artistic style. He is not a colorist who revels in subtle yarn blends; his work is bold, graphic, and focused on line and pattern above all.

| Archie Brennan, Sketch for Drawing Series LXXXIX: Seated Female Nude, 2009 and [tapestry] Drawing Series LXXIX: Seated Female Nude, 2009. 36.5" x 17.5" Both photos by Archie Brennan. |

For me, it was fascinating to read Archie's account of his brief flirtation with what he calls "the new wave" of fiber art that exploded in the 1960s and 1970s. These weavings eschewed pictorial imagery and exploited unusual and coarse fibers, hairy textures, massive size, and three dimensions, pushing weaving toward sculpture. This style has been rediscovered by weavers today. He writes that he realized, "The history of pictorial illusion in weaving was what intrigued me," and he revels in the "intimacy" of a tapestry that whispers rather than shouts, "savoring the delight of accumulating detail." Weavers today can choose to work in either of these modes, and it is helpful for those of us like me who are still trying to decide whether to weave "Objects or Pictures?" (or both?) to read his thoughts.

In a 1996 essay, Archie describes how today's weaving artists have sought to gain for tapestry a status equal to painting in the contemporary art world, and he thinks this is a mistake. He writes that his many woven postcards and parcels are partly intended to poke fun at this ambition. For him treating tapestry solely as art for the wall ignores a history in which in many places and times it has served other purposes. Tapestry as Art "neglects a potential role that is unique to tapestry" which includes among other elements, the element of time. In one of the several excellent essays by those who knew and worked with Archie, Mary Lane writes that "Brennan's pursuit of meeting tapestry on its own terms, his eschewal of descriptive color and his use of the grid allies with artists who favored the means of representation over the subject of representation." This is something to ponder. Indeed, I have read the book once, but I plan to reread it, cover to cover, soon, to further absorb Archie's views and clarify my own intentions and practice.

If you are a tapestry weaver, you may already be reading this landmark book and you will surely see several reviews of it in the coming weeks. Rebecca Mezoff has written a thoughtful review here. My post here does not pretend to be encyclopedic and I certainly cannot add any contextual details of having met or studied with Archie. But I hope this post suggests that if you take the time to read the text as well as savor the photographs, it will inform and challenge your thinking about what you weave, and why.