The tapestry world is abuzz with talk about the just-released book of the work and writings of weaver Silvia Heyden (1927-2015): Movement in Tapestry by Silvia Heyden. Her family and friends worked hard to complete this book that Silvia began in 2014, and they have done a beautiful job. It's not a book that you read once and then put away on a shelf. You'll want to keep it out so that you can dip into it now and again, enjoying and studying the gorgeous full-page color photographs of her work and re-reading her words. You can see by the fringe of post-its in my copy that I found much to ponder here.

As I was reading this book, I must have said out loud to Sam at least five times, "Silvia Heyden was a [flipping] genius." During her studies in the late 1940s with Bauhaus veterans Johannes Itten, Gunta Stözl and Elsi Giauque, she absorbed Bauhaus principles of the unity of medium, methods, and design. But upon her graduation, Heyden's mentors discouraged her from pursuing tapestry because it had mostly degenerated by that time into the slavish reproduction of paintings by non-weaving artists. Silvia's careful study of medieval European weaving led her to realize that in those tapestries the weaving and the image had evolved together, organically, under the fingers and vision of the skilled artist-weaver. She determined to discover a new language for tapestry that spoke in fresh, modern visual terms, that united, in true Bauhaus fashion, materials, technique, and image. "This particular harmony of content and execution, of art and craft, of means and meaning could be achieved only in my persistent dialogue with the loom" (p. 64).

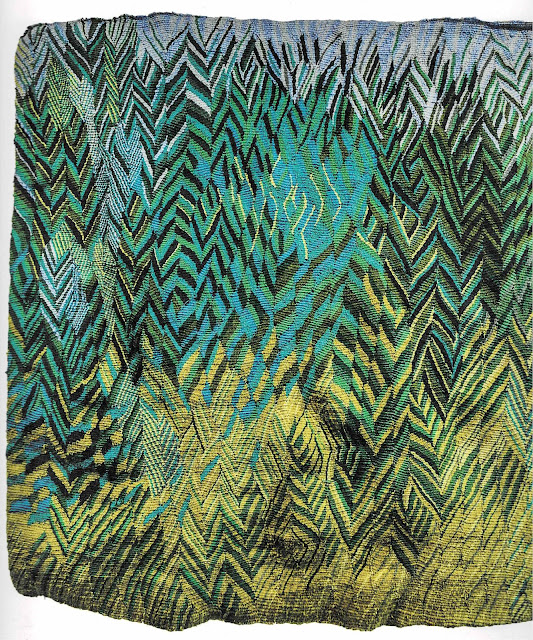

|

| Silvia Heyden, Through the Grass, 38" x 42," 1999. (Apologies for the scanner cropping the right side of the image. The book is bigger than my scanner bed!) |

Silvia recognized that she would need to develop her own vocabulary of woven forms to achieve this aim, and she spent ten years working on developing that personal vocabulary of triangles, half-rounds, stripes, chevrons and feathers. Ten years. For Silvia, a motif "is a weaving element that is not only repeated additively but that can in fact evolve into an entire composition" (p. 54). This in fact became her primary means of developing her tapestry designs. The motif IS the structure and image of the tapestry; not merely any repeated shape, it is a shape that organically grows from the weaving process. Silvia also determined that the conventional rules of tapestry weaving--that it result in a rectangular, flat textile in which the wefts travel only horizontally and totally cover the warp--need not apply. She favored colored linen warps that played an active visual role. She usually wove eccentrically, and while she tried to more or less balance the weft forces pulling the warp out of plumb, she was not concerned with whether the tapestry lay totally flat.

|

| Silvia Heyden, Diagrams of Diagonal and Rounded wefts, from Duke University exhibit catalog, 1972. |

Crucially, Silvia abandoned the traditional full-size cartoon attached to the weaving as a guide. If the weaving were to develop organically rather than as a reproduction of a pre-existing image, she had to wing it. "I must free myself from the dictates of the paper cartoon and rather depend on my inner eye and train my concentration." One of my favorite things about this book is that her small preparatory sketches, usually not much larger than 4" x 6" or thereabouts, are often reproduced next to the tapestry they inspired. We can see how the sketches, which are simply gestural indications of line direction and possibly value and color, often found expression in a new way in the course of the weaving. To keep track of how she was scaling up such a small sketch to her full-size, often five-feet-square tapestries, Silvia would place tick marks along the margin of the sketch and corresponding knotted bits of yarn along the warps of the tapestry.

|

| Silvia Heyden, Red Rhythm, 60" x 60," 1976 and preparatory sketches, largest is 5" x 4.5" |

For me, the prospect of weaving a large tapestry without a cartoon feels a bit like preparing to walk a tightrope over a river full of crocodiles. I am comforted to learn that Silvia was only able to totally abandon the cartoon after making about 200 tapestries. Her lifelong output was about 800 tapestries over 50 years. Eight. Hundred. Tapestries. If you are going to engage in a "persistent dialogue with the loom," you'd better, as Tommye Scanlin likes to say, "weave every darn day!" Tapestry is a long game. Learning basic techniques does not take long; learning to use those techniques in one's own voice is the work of a lifetime.

Since my own interests lately have been moving toward relief and 3D work, I was delighted to discover that Silvia made a number of small studies along those lines. She was always thinking "What if. . .," always exploring and pushing the limits of what tapestry can do.

|

| Silvia Heyden, Capriccios, approx. 21" x 21", 2006-2013 |

There is much to love about this book: The gorgeous full-page reproductions of Silvia's work. The inclusion of sketches, as mentioned above. The inclusion of Silvia's own writings and interviews about tapestry in an appendix. This is a definitive volume about Heyden's work and weaving philosophy; it completes in a most satisfying way the account in her previous book, The Making of Modern Tapestry: My Journey of Discovery, published in 1998.

There are a few quirks about the book that I found occasionally frustrating: No titles, dimensions or dates are given on the double-page spreads with the reproduced works; the reader must flip to the "Index of Paired Tapestries" to find that information. This was a deliberate decision to present the images on a clean white page, so fair enough. There is a long section at the end of the book, with small color reproductions of Silvia's tapestries, sketches and studies arranged chronologically--but again, these works are not identified by title. Finally, the text can be repetitive; we hear four times (in the Introduction and chapters 1, 2, and 4) how the Renaissance was the ruination of tapestry weaving. It's not clear to me who wrote most of the text of the book in which Silvia is spoken of in the third person, though Stephanie Hoppe is credited as the author of Chapter 3. And it took me awhile to figure out that italicized text throughout is Silvia's own words.

But these are minor quibbles. This is a book that every serious tapestry weaver will enjoy and learn from. Don't just take my word for it; read Elizabeth Buckley's blog for her take. I'm sure others in the tapestry community will be chiming in with their reviews as well. If you're wondering how to get your hands on a copy, don't waste your time looking for it online. It's available through Silvia's son, Daniel Heyden (email him to order).

It's fitting to close with Silvia's words: "When we no longer see a tapestry as a static image, but instead allow it to continue to beat in its progression, when this happens with purely woven means through the textile structure and the color of the thread, when detail and overall form are in such harmony that the outer form is the consequence of the inner transformations, then weaving, with its unique connection to craft and technique again becomes an independent art form." (p. 120)

This is wisdom born of a lifetime's dedication to the art of tapestry.